Starting in 2018, Transparency International (TI) Rwanda began to support national efforts to produce the country’s 2019 VNR. From the beginning, TI Rwanda was keen to emphasize the linkages between corruption and the SDGs and so produced

a scoping study on the effect of corruption on national efforts to meet SDGs 1, 3, 4, 5, 8 and 13.

While corruption is relatively high on the national agenda, key SDG implementers in line ministries are not sufficiently sensitized to the risks that corruption poses to the country’s targets under the 2030 Agenda. To address this issue, TI developed a comprehensive approach intended to: (1) produce evidence that corruption hinders progress towards national development goals; (2) identify innovative mechanisms to mitigate corruption risks in SDG implementation; and (3) track the effectiveness of these measures over time jointly with SDG implementers.

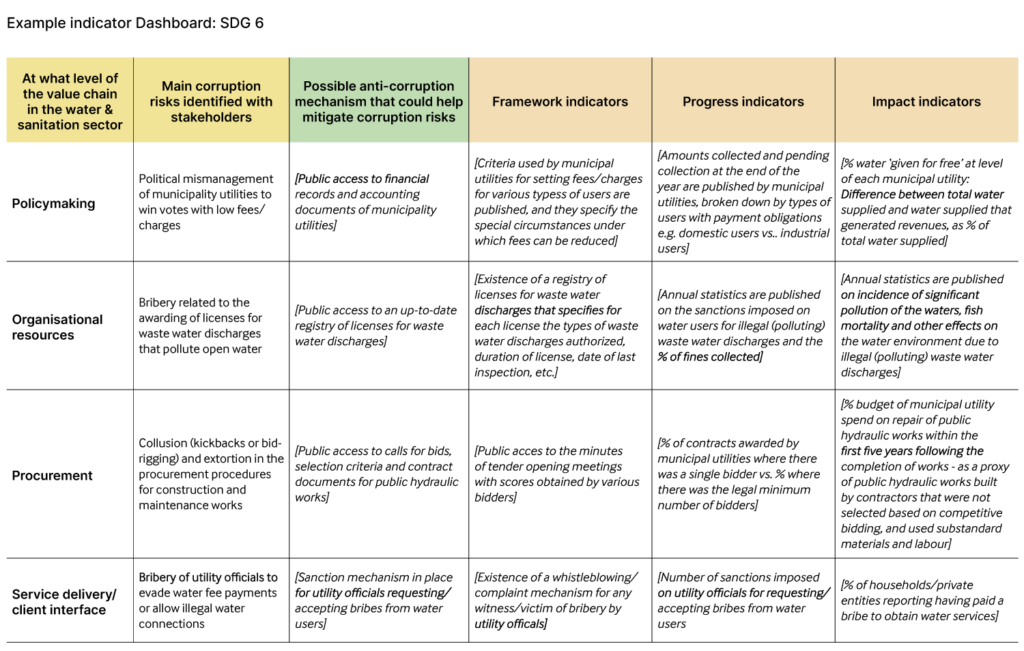

The approach involves producing a one-page ‘dashboard’ that combines official and non-official data sources for each SDG relevant to TI Rwanda’s work. By consolidating various scattered datasets into one coherent framework, the dashboard provides a highly actionable roadmap to reduce corruption vulnerabilities in SDG implementation. The approach involves a three-step process intended to bring together the various data and expertise used by individual programmes into a single dashboard tailored to individual SDGs.

First, an initial corruption risk assessment is conducted in collaboration with sectoral experts to identify and prioritize the main risks at each stage of the SDG sectoral value chain, from the policymaking level to the point of service delivery. Once risks have been mapped for each SDG of interest, the second step is to launch consultations with government, businesspeople and affected communities to match each prioritized corruption risk to corresponding anti-corruption safeguards designed to mitigate that risk. The final stage involves producing a monitoring framework that pairs each anti-corruption safeguard identified to a combination of different indicators that consciously draw on a range of data sources to provide a holistic appraisal of the effectiveness of anti-corruption mechanisms in place.

Synthesizing this information into the dashboard’s monitoring framework allows SDG implementers to track whether their programmes are becoming more or less vulnerable to corruption, based on an overarching conceptual model that is sensitive to local context. While the tool is in the early stages of implementation, it is already clear that it lends itself to evidence-based advocacy, as it provides an at-a-glance understanding of the corruption risks that can undermine progress towards individual SDGs.

That each dashboard’s framework draws on different data providers, including government sources and third-party assessments as well as data produced by the organization itself, is a strength of the tool, as it allows for the verification, comparison and triangulation of the official narrative as told in the VNR. As such, it is clear that the country’s VNR is simply a first step in the process and that the official indicator set agreed upon by the IAEG must be complemented with more locally meaningful data to ensure transparency, accountability, and participation in the 2030 Agenda.

Take-aways and Going Forward: TI Rwanda believes that the tool could be further developed into a multi-partner project by which different organizations input different data, building on the monitoring processes of each. Ultimately, the tool could be transferred to impartial government agencies, such as NSOs, to institutionalize the monitoring of governance issues in SDG implementation. Another possibility involves modifying the dashboard to turn it into a tool for community action to help citizens hold local leaders accountable in reporting corruption incidences.

A key

lesson has been the pivotal importance of outreach; early communication is needed to ensure that relevant stakeholders feel addressed and know that the tool is holding them to account for their performance on specific SDGs. So far, TI Rwanda has combined desk research with online expert surveys, followed up by workshops to assess the severity of risks identified. Hosting small multi-stakeholder workshops with experts from government, the private sector and civil society during the process of developing each SDG dashboard was beneficial. The reason for this is that involving partners at an early stage helped to nurture ownership and buy-in from government and non-government representatives, which also facilitates subsequent access to the data needed to monitor progress.

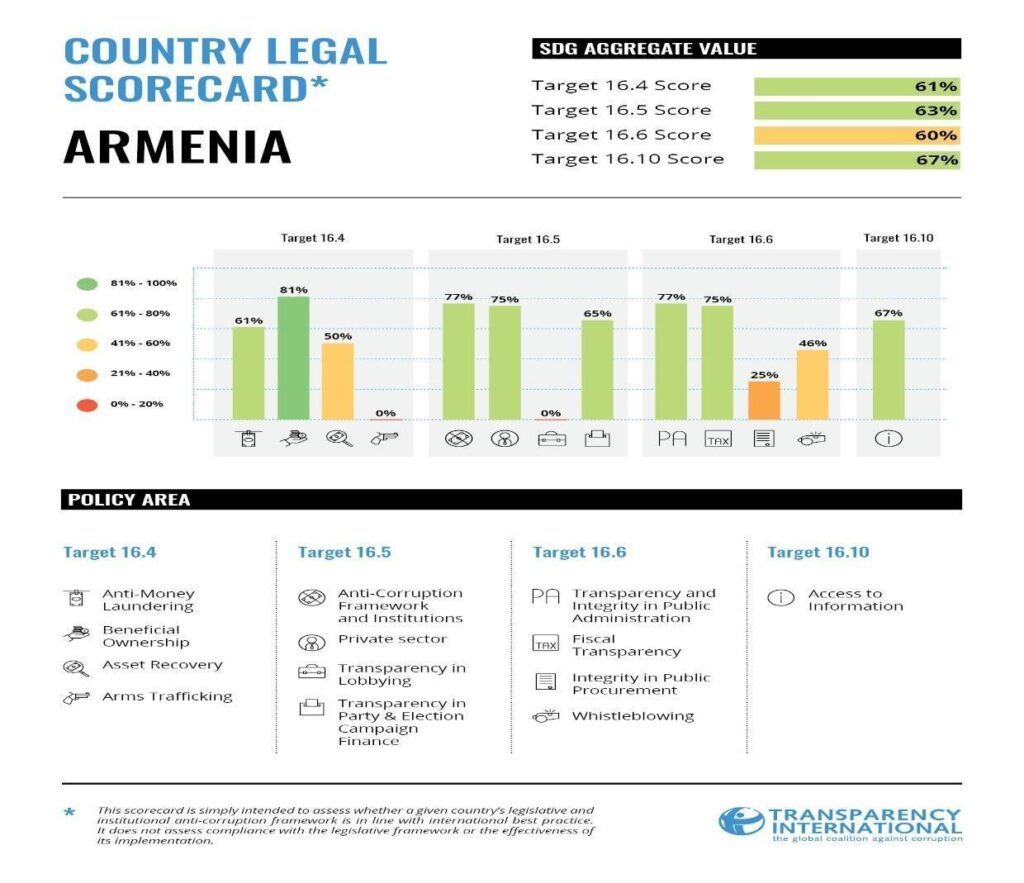

* An Example of a Country Score Card is included in the Appendix.

* This case study was provided by Transparency International Rwanda in 2019.