Since 2016, the

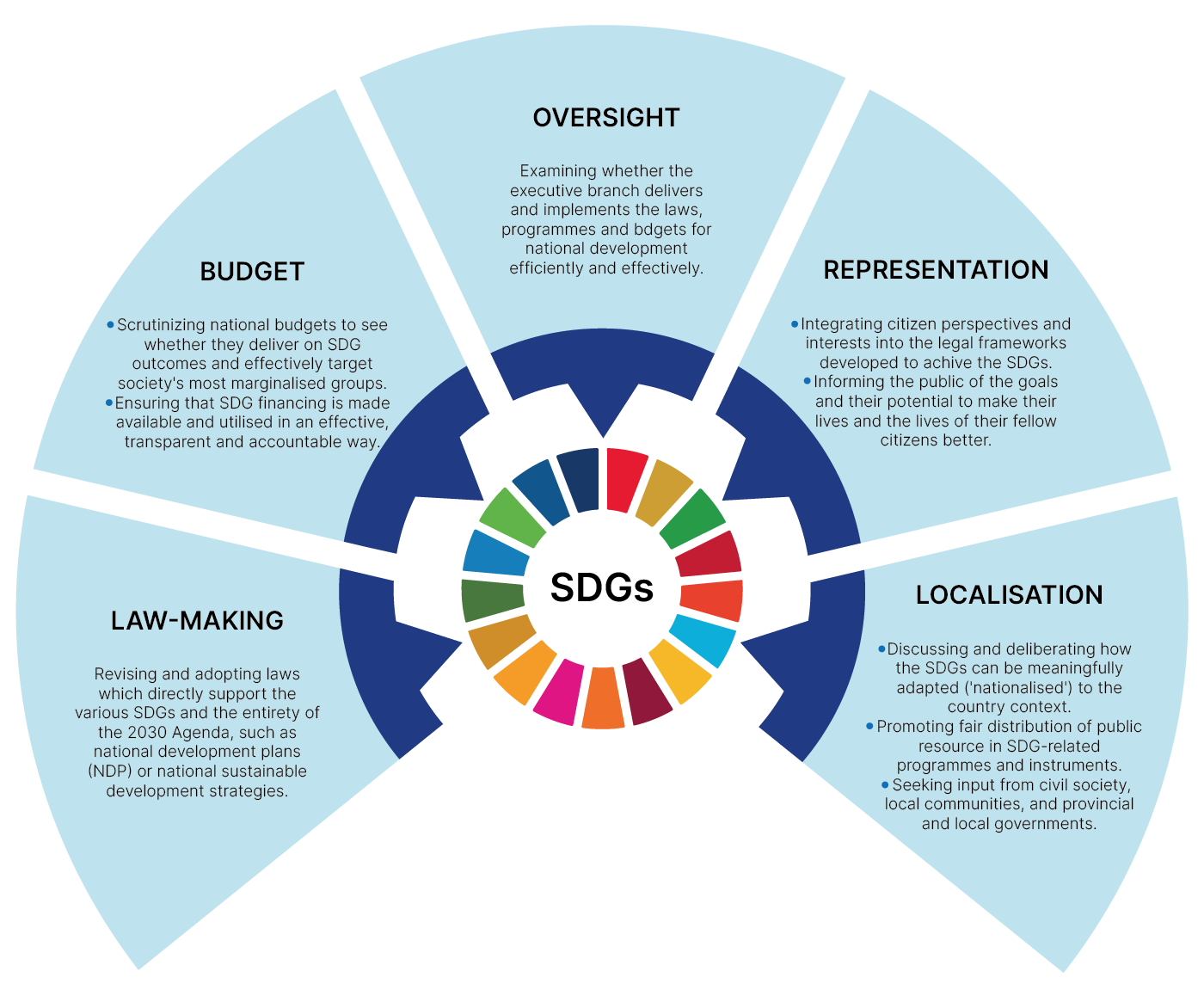

Fijian Parliament has undertaken a series of initiatives to promote and ensure progress on SDG implementation. Recent efforts have focused, in particular, on mainstreaming and integrating the SDGs into its work and the work of Parliamentary Committees as a means of exercising its executive oversight role in implementing the SDGs and legislative function.

Building upon a

2017 self-assessment, Fiji’s Parliament, along with partners, launched

a guidance note in 2019 on integrating the SDGs across the work of Parliament Committees, addressing the alignment of committee systems, structures and mandates to SDG-linked national development priorities, with baselines and agreed reporting processes on progress. Additional focus was placed on the use of SDG indicators in tracking progress towards SDG and NDP targets as Parliament and Parliamentary Committees scrutinize legislative bills, annual reports, sector performances, public expenditure and engage with the public. While SDG 16 suffers from a lack of baseline indicators as reflected in its National Development Plan, Committees have nonetheless been able to move forward in support of SDG 16, including working with Fiji’s NHRI on addressing police brutality and drawing from Annual Reports of institutions or agencies that fall within their purview.

The Standing Committees primarily focused on SDG 16 are the Committee on Justice, Law and Human Rights Committee and the Committee on Foreign Affairs and Defense. In exercising their oversight role, these Committees review the Annual Reports of institutions or agencies that fall within their purview and then ask questions of those entities, with responses and follow-up actions carried out in return.

For example, based on its 2016, 2017 and 2018 Annual Reports, the Committee on Justice, Law and Human Rights asked Fiji’s Human Rights Commissions how the Commission has sought to advance SDG 16, including in following up on complaints and allegations of police brutality and misconduct. In return, the Commission highlighted its actions and the responses of relevant institutions, whether Fiji’s Police, its Corrections Service or the Judiciary, to allegations and grievances noted.

While the work of Parliament on SDG integration and the VNR are separate, parallel processes, Fiji’s 2019 VNR placed significant focus on the rule of law as an enabler of development, highlighting the underlying importance of SDG 16 to the work of the Committees and to the NDP, despite a lack of data.

Take-Aways and Going Forward: Solving for Data. The lack of local baseline data and local targets in Fiji’s NDP for certain SDGs should not deter Parliament from working through its committees to push government ministries and departments to set targets and goals even outside of the NDP. This would allow Parliamentary Committees to monitor ministry and department progress in achieving those SDGs and targets through annual reports tabled by those entities to parliament. In the absence of nationally-set baselines, targets and reliable data, Parliament should consider using global targets (or regional targets, if existent for a particular SDG) as reference in conducting government oversight.

* This case study draws from 2019 interviews with UNDP, Fiji.